The risk Britain is no longer willing to take

Why the downside of starting a business now outweighs the attempt

Written by Lewis Thomas

Despite years of policy intervention, the conditions required for people to take risks - and to fail safely - have been weakening.

Since 2020, the UK Parliament’s official record shows more than 4,000 uses of the term “high street” across debates, questions and committee proceedings. A simple, stark measure of how persistently these social and economic spaces have occupied Westminster.

This attention matters not because high streets are symbolic, but because they are everyday places where policy decisions intersect with the lives and work of ordinary people.

Governments of all stripes have spent years layering intervention upon intervention: from the 2011 Portas Review and early innovation funds, to the Future High Streets Fund and Towns Fund, statutory powers and investment through the Levelling-Up and Regeneration Act, High Street Rental Auctions, and most recently Labour’s Pride in Place programme.

And yet despite sustained attention, multiple reviews, and billions of pounds in targeted funding, many UK high streets, town and city centres are in visible decline.

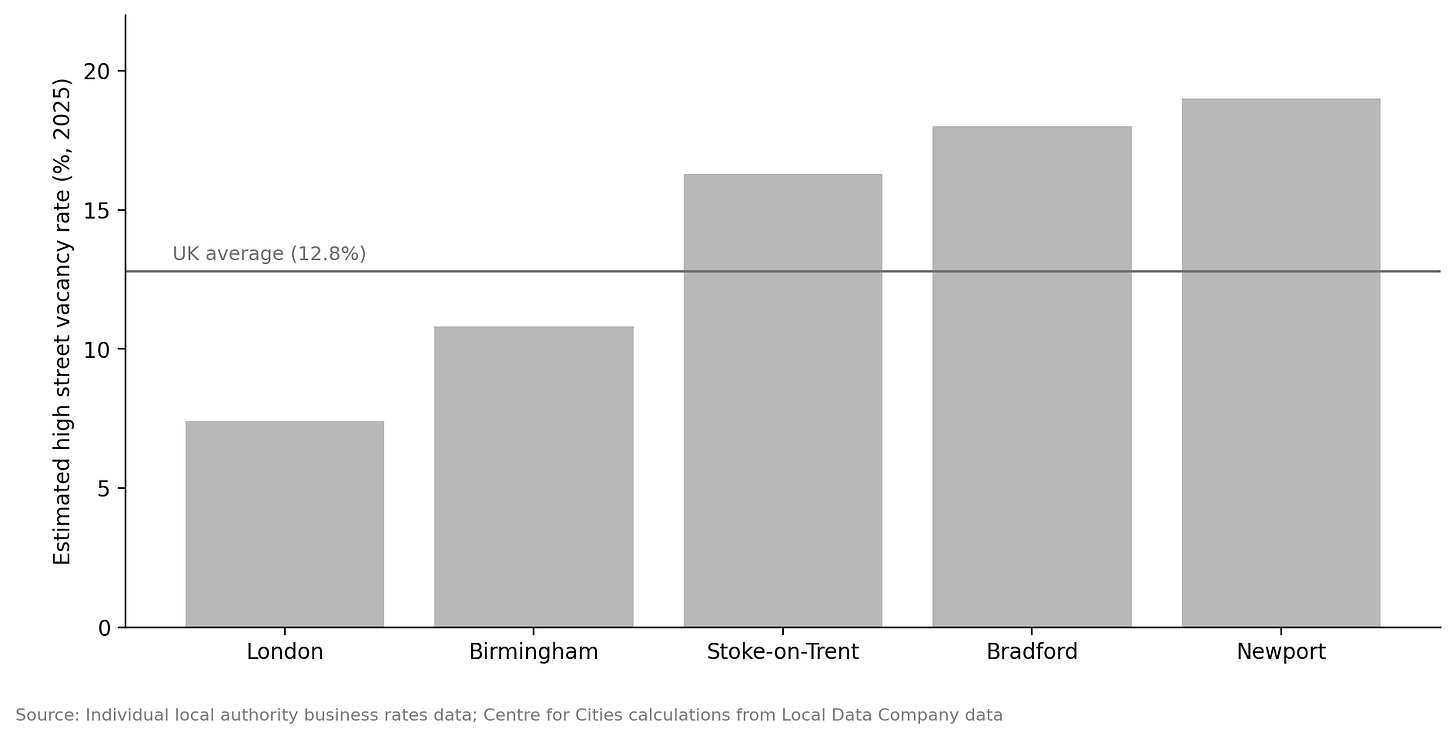

Using the most recent data available, Centre for Cities shows that in places like Newport, Bradford, or Stoke, vacancy rates sit close to 20% - meaning one in five shopfronts stands empty.

Even the lower national average of around 13% tells its own story.

On a typical British high street, roughly one in every eight units is closed: shutters down, or windows polished into slow circular swirls that keep the space presentable while concealing the emptiness inside; “To Let” signs lingering longer than the property agent intended.

The pandemic brought this fragility into the light of day, compressing years of pressure into months. For businesses operating on thin margins, this exogenous shock - and its secondary effects, from collapsing footfall to accelerated behavioural shifts - pushed them beyond viability.

Longer-running secular trends also continue to reshape the high street. Chief among them is the steady expansion of online retail, which now accounts for around 28% of all retail sales in the UK. This share jumped during the pandemic and has since stabilised at a materially higher level.

The combined effect of the pandemic and the shift online has been to permanently alter the economics of physical retail, in particular.

Brick-and-mortar businesses are now competing for a smaller share of discretionary spend, fragmented across online platforms, out-of-town retail, and experience-based consumption. While demand has not disappeared, it is thinner, less predictable, and less anchored to physical place.

For high street businesses, this matters because their cost base has gone the other way.

Wholesale energy costs for UK businesses spiked dramatically in 2021–22, with electricity prices rising sharply and gas prices more than doubling at their peak. Both remain materially higher than pre-pandemic levels. Labour costs have also risen, with the National Minimum Wage increasing repeatedly and, under current plans, set to be uplifted again later in 2026 to £12.71 an hour.

Raw materials show similar upward pressure: global coffee bean prices, for example, reached near multi-decade highs in recent years.

For a small coffee shop, that amounts to a triple squeeze - paying more for beans, more to heat the premises, and more in wages - all while competing for a consumer that is also under pressure.

The instinctive response to these strains is to reach for further policy levers: new, but often the same played-out incentives, targeted funds, or regulatory tweaks designed to revive local enterprise and footfall. The sheer volume of parliamentary debate and successive initiatives over the past decade suggests concern - and perhaps misdirection - rather than neglect.

And yet the ongoing deterioration of our urban centres and high streets points to a deeper, more unsettling problem.

Repeated intervention has struggled because it continues to treat the high street - the heart of our towns and cities - as a retail, leisure or property challenge to be managed, rather than as a risk environment in which people decide whether it is worth starting, or sustaining, something at all.

It is not just a question of symptom management, focusing on addressing footfall or funding, but of confidence: the belief that opening a café, restaurant, shop, co-working space, or pub is a risk worth taking, and one that will not be unfairly penalised by forces beyond the owner’s control.

This uncertainty for existing and prospective small business owners continues to be bred by a policy and economic framework that pushes financial volatility and operational burden downwards - away from institutions and onto the smallest actors least able to absorb it.

Recent reforms to UK employment law and labour protections offer a clear example.

Many of these changes have been introduced for legitimate reasons, strengthening worker security, reducing exploitation and expectations around fairness at work.

For a small business on the high street, however, labour is no longer a flexible resource but a fixed commitment. Higher minimum wages, increased employer national insurance contributions, changes to holiday pay rules, and more formalised dismissal processes all raise the cost and administrative burden of taking someone on. None of these shifts are inherently unreasonable. But together, they alter the risk calculus dramatically and can make it harder to run a small business.

The tension is not between fairness and exploitation, but between systems designed for scale and environments that depend on operational flexibility and small-scale experimentation.

A 20-cover restaurant that may once have relied on seasonal, flexible student staff is now expected to manage employment risk through the same processes as larger chains, which can spread these fixed administrative and compliance burdens across many sites and staff, often with in-house specialists; for a single-site restaurant, the same rules demand the same time and expertise, diverting scarce time, money and attention. It’s a mismatch.

In an environment where demand fluctuates and margins are slim, these changes are reducing the room to experiment, adapt, or recover from small mistakes.

The result is predictable: fewer hires, shorter hours, delayed expansion - or the decision not to open at all. It’s why so many units remain empty, devoid of economic lifeblood.

Recent surveys from bodies like the Federation of Small Businesses and British Chambers of Commerce reflect this, with small employers frequently citing rising labour costs and new employment protections as among the top barriers to expansion or even maintaining headcount, contributing to subdued hiring intentions into 2026.

Another way this asymmetry of risk shows up is in how fixed costs are imposed on high street businesses, mostly regardless of performance or demand.

Business rates, for example, do not flex automatically when footfall falls or margins compress. Levied on shops, pubs, cafés and other premises, the tax is based on location and property value, making it one of the largest fixed costs many high street businesses face.

Reform of the business rates system has long been debated as a potential tool to ease pressure on smaller operators. Yet in practice, relief has tended to be temporary and conditional, rather than structural. With pandemic-era support schemes now unwinding and the next revaluation cycle due in 2026 - based on 2024 rental values - some high street businesses face the prospect of higher rateable values irrespective of where we are in the wider economic or consumer cycle.

That disconnect became particularly visible earlier in January for pubs, where planned changes threatened a cliff-edge moment for already fragile operators. The government’s subsequent reversal softened the immediate impact, but it also underscored the issue: a system that is politically charged, reactive, and difficult for small businesses to plan around with confidence.

Focusing primarily on treating the visible symptoms of this system has left permanent scarring for business owners and those considering starting a new venture. Official business data shows that business deaths have often outstripped births since 2020, resulting in a net loss of nearly 15,000 enterprises UK-wide - a reflection of the heightened downside that deter new businesses.

The data captures the businesses the UK has lost. The more revealing damage lies elsewhere: in the number of people who would like to take space on a high street and start something, but decide not to. The most consequential losses are no longer the closures we can count, but the attempts that never happen - deterred by a system that is rigid and difficult to navigate, and where failure is not a reversible chance for learning, but a swift, public, and financially and psychologically difficult experience to recover from.

The absence of new ventures is most visible in the units that remain vacant, but its effects extend well beyond empty shopfronts. High streets are not just economic corridors; they are social and civic spaces shaped by daily presence and routine activity. As legitimate activity dwindles, those spaces become less predictable and more vulnerable to antisocial behaviour and crime.

In England and Wales, police-recorded shoplifting offences hit 530,000 in the year ending March 2025 - the highest level since current recording began. This is no longer peripheral behaviour. It has become part of the everyday experience of town and city centres: alarms sounding, security staff intervening, and a sense that public space is less orderly than it once was.

Bedford offers a useful case study in how local confidence collides with national constraint.

Peter McCormack, a Bedford-based business owner, previously funded a private security pilot in the town centre after opening a café and witnessing, in his words, the scale of disorder “when you sit there all day.” The initiative involved hiring licensed security staff at a cost of around £10,000 per month, funded privately, with the aim of restoring visible order and making the high street more safe and accessible again for families and small businesses.

For a period, the intervention appeared to work. Shopkeepers reported feeling safer and footfall improved on pilot days. But speaking more recently on What Bitcoin Did, McCormack explained that he had stopped the effort. “So I gave up,” he said, concluding that the problem was no longer local. “I realised it didn’t matter what I did in Bedford - everything is downstream of central government.” In the same discussion, he described deciding not to proceed with opening a further business - a pizza restaurant - despite having capital available. As he put it in an earlier podcast:

“I’ve got money on the side now, ready to open more businesses in the town, and I’m sat there going, I don’t know if I can turn a profit here because of government.”

McCormack’s experience is revealing because it is not one of inexperience or risk aversion. Alongside his other ventures, he has overseen successive promotions with football club, Real Bedford FC - a capital-intensive, operationally complex project with uncertain returns. And yet even individuals willing to take on that level of financial exposure are now choosing not to extend themselves on the high street. The decision not to open another business is not a retreat from enterprise, but a response to a set of conditions that no longer feel proportionate or navigable.

Our high streets now expose not just decline, but the erosion of confidence in the act of trying. Not just for well-resourced serial entrepreneurs, but for first-time founders and small operators deciding whether to take space and test an idea. Confidence is not built by just protecting incumbents or endlessly refining support schemes, but by resetting the risk environment itself - ensuring a new business can fail without becoming a financial, legal or reputational catastrophe.

Until the asymmetry eases, where the downside of trying feels proportionate to the upside, every vacant high street unit will continue to stand as quiet evidence of risks not taken: not just closures we count, but the ventures, experiments, and small acts of confidence that never begin.

Very informative article