This month used to take years

Sovereign debt, reactive policy, and watching it unfold in real time

Written by Lewis Thomas

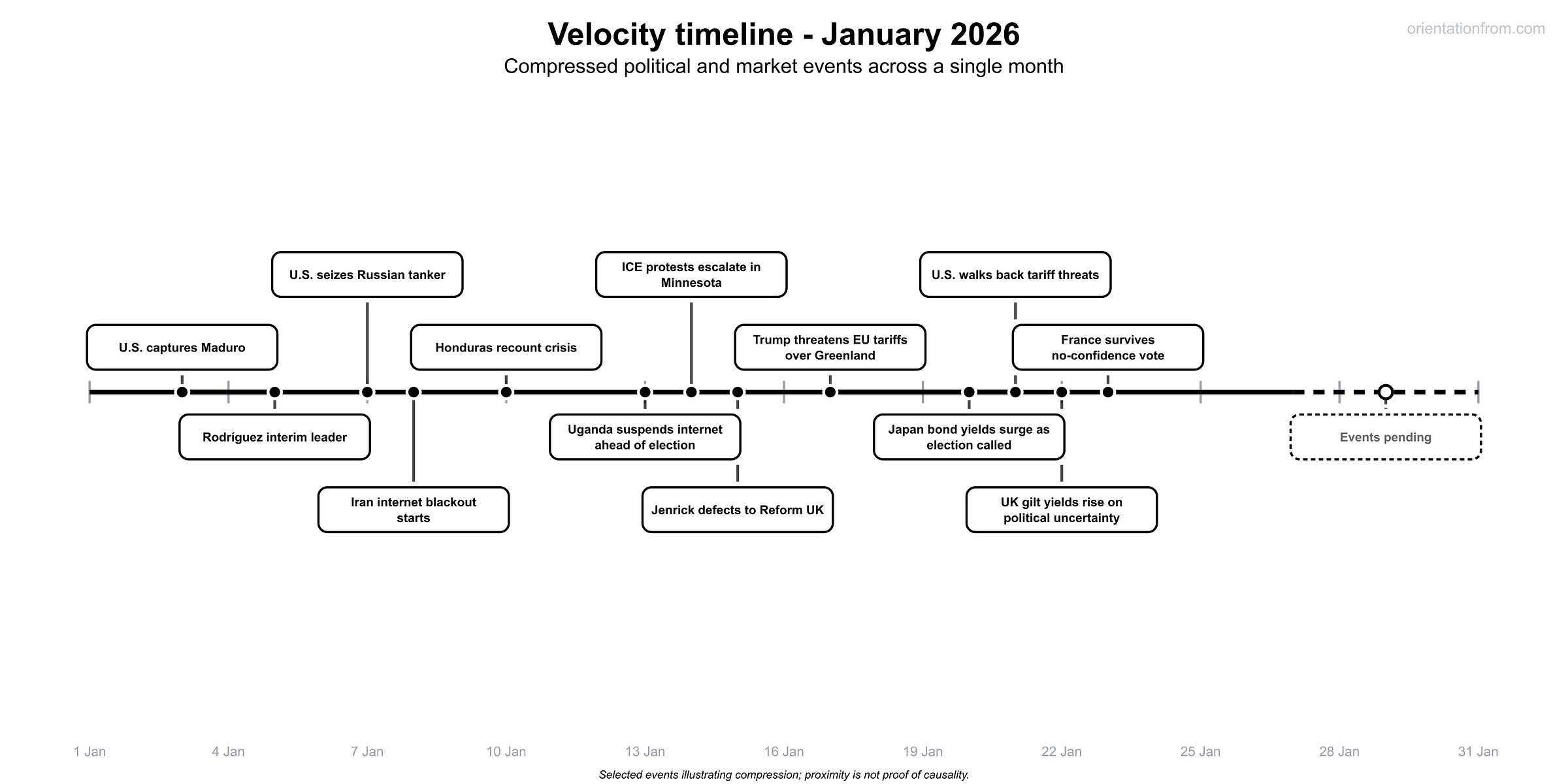

This is January 2026. Not an exceptional month, nor cherry-picked chaos, but so far 27 days of continued global volatility:

The United States captured Venezuela’s Maduro in an overnight raid. Trump threatened tariffs over Greenland, then walked them back days later. Multiple governments shut down the internet amid unrest. Japan’s bond yields surged as elections were called. UK gilt yields rose amid renewed political uncertainty. France survived its latest no-confidence vote.

These aren’t random disruptions, taking place in different timezones or continents. They are interconnected: each political, economic or social rupture creating the conditions for the next one.

Shared financial constraints, hypersensitive markets, and fragile political legitimacy mean these shocks no longer dissipate; they transmit.

Previously, this systemic breakdown emerged as a series of ‘temporary’ crises spread across years. We’re now compressing that pattern into weeks, and the equilibrium can’t be restored between shocks. And the month isn’t even over.

Speaking at Davos 2026, Bridgewater’s Ray Dalio was clear in his assessment:

”The monetary order is breaking down. What I mean is that fiat currencies and debt as a store of wealth is not being held by central banks in the same way. And that there was a change. The biggest market to move last year was the gold market, far better than the tech markets and so on.”

Dalio’s statement is cutting. It gets to the crux of one of the foremost issues we are facing: the indebtedness of our governments.

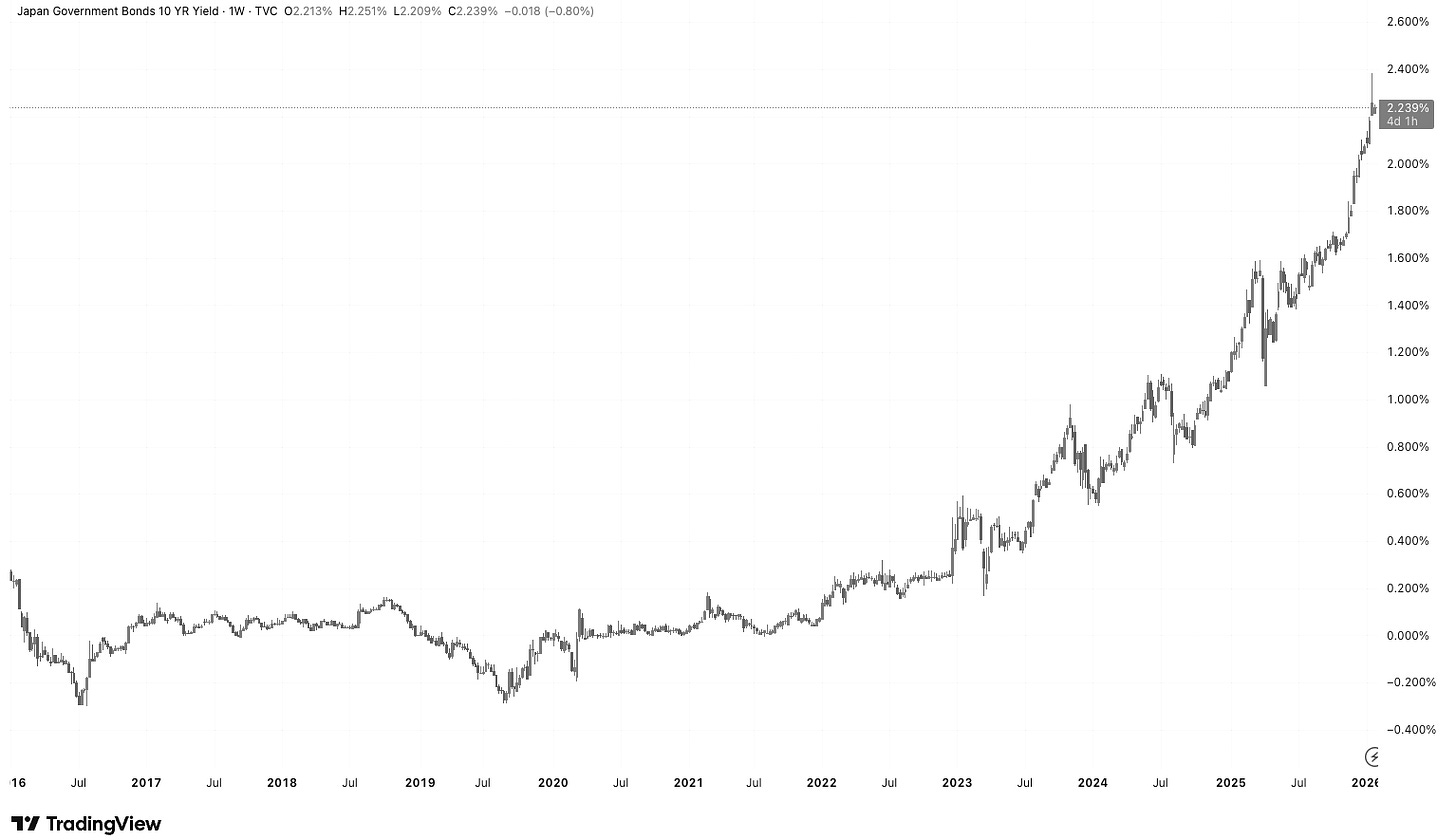

The US holds $38 trillion in debt - more than its annual GDP. Japan’s debt-to-GDP ratio sits at 230%, twice the US level. In the UK, more than £1 in every £12 of government spending goes to servicing debt interest payments alone.

Countries are currently moving through predictable stages:

Hedge finance: Cash flows cover all obligations (principal + interest)

Speculative finance: Cash flows cover interest only; must refinance principal

Ponzi finance: Cash flows insufficient even for interest; survival requires rising asset prices or continued borrowing

For most governments, we are now moving from speculative finance, to the Ponzi finance stage, where a drawdown in asset prices is damaging to individuals, and structurally destabilising for governments.

This isn’t a literal equivalence - sovereign states can tax and print money - but the underlying logic is familiar: when obligations outpace organic cash flows, stability becomes contingent on confidence, asset prices, and continued refinancing rather than resolution.

As part of a global market sell off, the S&P fell 2.1% after Trump’s Greenland threats and EU tariff announcement. A modest decline, but as asset prices fell and the potential impact on pensions and portfolios became visible, he reversed course within days - consistent with Ponzi logic: policy responding to prevent a further cascade.

Entering this new territory means politicians face the choice of either allowing a bigger debt crisis to unfold, or postponing it through currency debasement.

These two deeply unattractive choices continue to be played out globally.

The evidence is materialising through long-dated bond yields rising even as policy remains accommodative, with central banks also continuing to increase gold holdings and talk openly about diversification away from dollar concentration. Some investors are also seriously treating bitcoin as an alternative hedge.

As this month shows, policy is becoming desperately reactive, with presidents and prime ministers lurching to prevent collapse rather than building coherent strategy.

And we’re watching it happen in real-time.

What is novel about the current situation compared to the past isn’t just the speed of these shocks or the corresponding reactions, but the extreme visibility of them happening.

Historically, this breakdown was conveyed, even mediated, through gatekeepers. Some of these were logistical: the newspaper was delivered once a day, the evening news didn’t start till 6pm.

Others were more structural. A journalist, their editor, even a newspaper’s ownership may have dictated what stories you saw, and more importantly, how they were told.

These buffers are now disappearing.

The democratisation of information means there are fewer filters between current events and global awareness. Anyone can now document and discuss the breakdown in real-time.

This visibility is a threat to economic and political power.

When the online feed is infinite and ungated, governments have one tool left: kill visibility itself.

We’ve seen this censorship twice already in January.

Iran has entered its third week of internet blackout - one of its most severe - as protests against the Islamic Republic intensified. Uganda also suspended internet access two days before its general election as President Museveni sought a controversial seventh term.

This month gives us a glimpse of what escape velocity looks like, where traditional systems struggle to pull themselves back from the brink: governments under pressure to pay back the interest on their trillions in debt. Central banks diversifying away from the currencies they’re meant to defend. Presidents reversing policy within days because markets can’t tolerate even modest corrections. Regimes shutting down the internet because visibility itself has become destabilising.

Previous generations experienced systemic breakdown through curated retrospective narratives, or if in real-time, through editorial filters. We’re watching this one with full, unmediated visibility.