Create, over criticise

The case for trying it yourself

Written by Lewis Thomas

After three essays on what's breaking, a look at what individuals can now do about it.

My first three Orientation essays were moody.

They weren’t written to be pessimistic, but rather reflect reality: how business risk in the UK is being pushed downward, hamstringing smaller firms, and why our political leaders are becoming increasingly erratic in response to fiscal pressure. There was also a more exploratory piece, inspired by my experiences with AI memory, and the development of systems that don’t forget.

It would have been easy to follow in the same vein again. Not least considering the corruption laid bare this week within British politics and ‘high society’.

But diagnosis without response is just commentary, and the more honest reaction to institutional failure isn’t outrage. It’s to create.

Cynicism also misses the bigger picture unfolding - that we’re in a pivotal moment where the boundaries of what one person can do are being reconfigured and we don’t yet know where they will stop.

Part of what’s destabilising centralised institutions like governments and big business is that the capabilities once associated with scale – resources and financial backing – no longer depend on it. Instead, individuals are now being equipped with powerful new technologies, increasing access to knowledge, skills and networks at a cost that would have been impossible a generation ago.

Where these lines cross, individual action is becoming a powerful opportunity. Not in a heroic, let’s fix all the failing systems kind of way, but a human response as individual capability - to build, create, and solve problems - rises.

This decades-long transition, set in motion by collapsing coordination costs, is accelerating.

In 1990, an international phone call cost more than a pound per minute. Now billions coordinate across borders for effectively nothing. Expensive and slow dial-up home internet now operates wirelessly at hundreds of megabits. Geography is no longer a barrier to collaboration and the economic impact is material: startup costs fell from $5 million in 2000 to under $50,000 by the 2010s. Capital-intensive infrastructure – office space, physical servers, telecommunications – is optional following the development of online systems.

Fundraising has followed a similar pattern. Crowdfunding platforms can bring together large numbers of small backers with founders they may never meet. In the UK, crowdfunding has helped finance over 2,500 companies, including Black Sheep Coffee and digital bank Monzo.

Tools have also become more affordable and accessible.

A smartphone can now function as camera, editing suite and distribution channel - allowing users to capture content and circulate it in minutes.

One of the most important developments has been the growth of open-source software. As a result of the ingenuity and graft of volunteers, infrastructure that was once proprietary and expensive is available to all, often for free. Take Linux, an operating system built by the open-source community, now underpinning Android and running the fastest supercomputers.

The latest stage that we’re currently witnessing is the democratisation of knowledge.

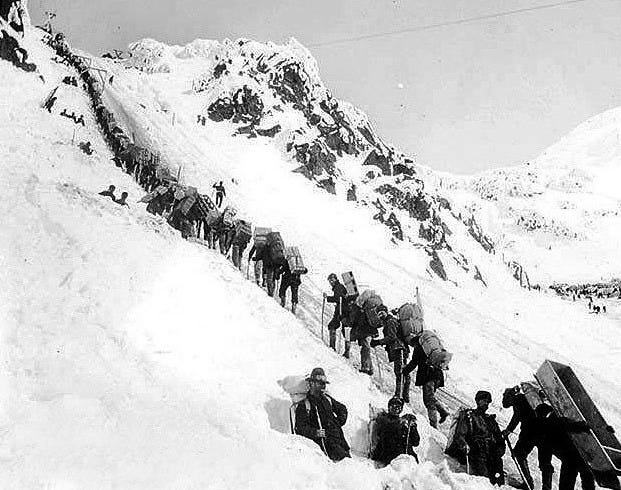

This began with the internet and the emergence of platforms such as Wikipedia and YouTube that function as interactive, continuously updating shared archives. Wikipedia alone hosts millions of articles. My latest rabbit hole is reading about the Klondike Gold Rush, and the journeys of prospectors over the Chilkoot Pass toward boom towns like Dawson City or Skagway - the latter infamous for its lawlessness and economy of drink, gunfire, and prostitution.

Formal education has also found a home on the internet.

The Open University, founded in 1969 as a distance-learning experiment reliant on broadcast media and postal services, delivers the bulk of its teaching online and has educated more than 2.3 million students worldwide.

All of this change has come with the ability to actually do things, not just read about them.

Platforms like GitHub are allowing developers worldwide to share solutions to problems in real-time, learning by doing rather than through formal credentials.

During the ventilator shortages of early COVID-19, open-source designs circulated online within days: makers were able to build functional devices in weeks, while official procurement channels were stalled.

These forces - coordination, tools, and knowledge - are currently converging through artificial intelligence. For less than the cost of a round of pints, an individual is today able to access capabilities that once required years of education, specialist support or significant resources.

Whether researching, writing, coding, or analysing, AI introduces a new dynamic. The work still requires judgment and direction; technical knowledge helps, but the threshold has fallen so that someone can learn basic coding concepts and generate functional code in the same session.

The capability gap between individual and institutions is narrowing measurably.

For solo entrepreneurs and small teams, it levels the playing field. Not guaranteeing success by any means, but giving them new ways to compete.

I left a corporate role recently. It was a large law firm, and was forward-looking when it comes to AI. While it had even introduced AI-usage metrics tied to the firm’s bonus structure, adoption was patchy and mainly limited to CoPilot. A different world to what’s being built outside those walls, led by agile, lean teams with less to protect and more to gain.

Industries such as law will take longer to disrupt. The strict regulatory conditions, complexities and nuance of legal matters require the expert input of humans, and for good reason. Those with less of a technical moat are, however, under pressure.

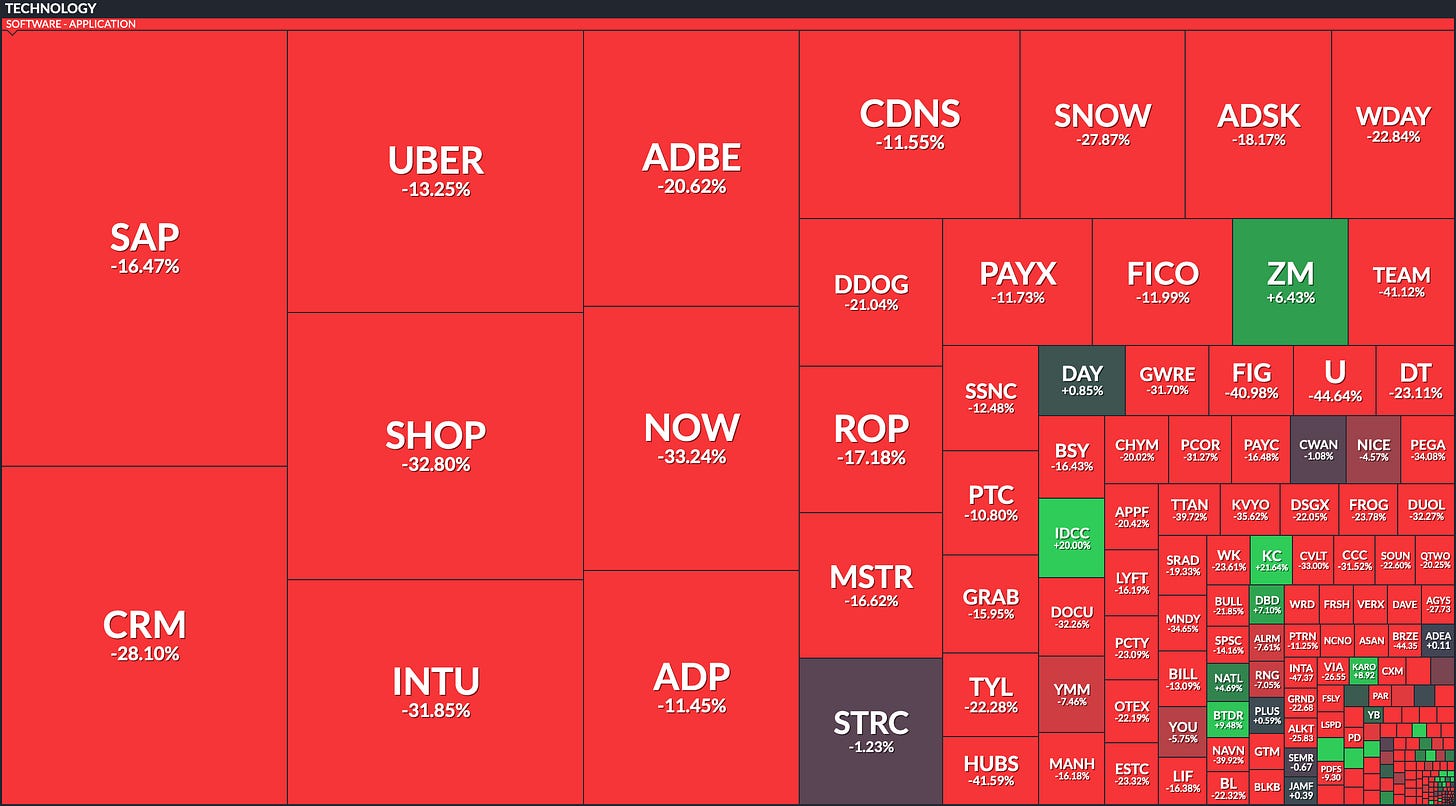

We are already seeing this in the software ecosystem, where the share prices of giants such as Adobe and Salesforce are sliding.

More than $950 billion of market capitalisation was recently erased from the S&P 500 software and services group. No doubt some of this is overdone, but it shows how the thinking is changing - at least in the mind of investors - and that in a world where an experienced coder can call on the support of simultaneous AI agents, the time and cost involved in creating software is lower.

Companies that once outsourced everything to enterprise software vendors can now build more of it themselves - tailored, cheaper, and increasingly viable.

There’s talk in Silicon Valley of billion-dollar solo companies - one person, no employees, built entirely on AI. It isn’t impossible now that the gap between having a vision and being able to test it has never been smaller. We’ll still fail as fast; success hinges on how good the idea is, but finding out may no longer require a large team or millions in venture capital funding.

AI’s impact on business is front of mind, but its reach will extend to other realms, altering politics and public policy. This includes potentially supporting new kinds of civic action that previously most people never get around to pursuing, not because they didn’t care, but because turning concern into action felt impractical alongside a day job, bills, and limited spare time.

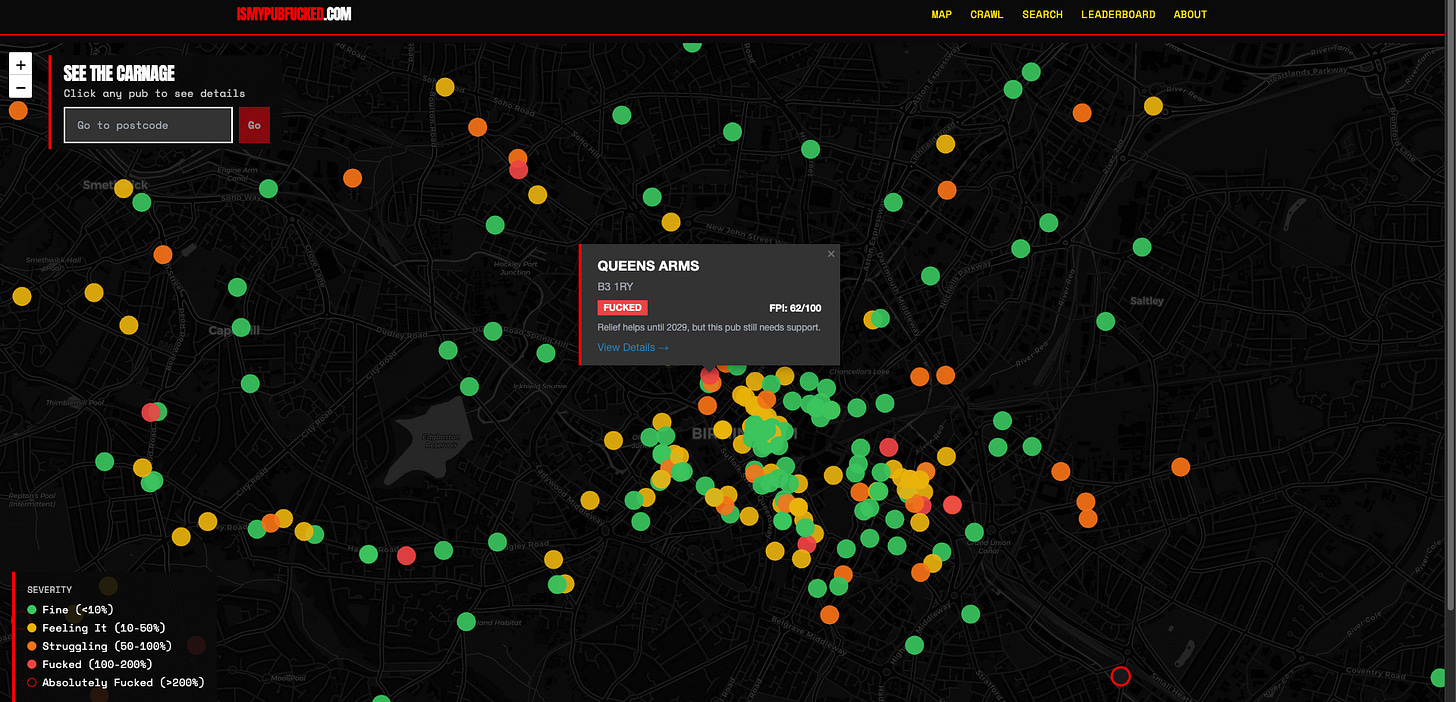

We caught an early signal of this in January with the launch of ismypubf---ed.com.

Concerned about the impact of potential business rate increases on Britain’s pubs, Ben Guerin decided to do something about it. On his commute, Guerin came up with an idea for a website that would highlight the impact of the rates, which to some pubs would have been last orders.

He shared the plan with Claude Code, using publicly available Valuation Office Agency rateable value data. Running in the background, hours later the site was live: a colour-coded map of 46,000 pubs, searchable by postcode, estimating how severely each one was affected.

For the Queens Arms, one of my locals, the website showed that the pub’s rateable value could have increased 107%, giving it an FPI score of 62/100. Otherwise, f*cked.

While Guerin has a developer background, this shows how AI could be the difference between a project getting off the ground or not. In this case, it did. The website recorded more than 400,000 visits, circulating widely on X and Reddit, and earning the support of publicans countrywide.

Amid wider industry pressure, the government announced a support package days later. Whether it saves those pubs facing extreme rises remains to be seen. But as a result of one person, one tool, and one idea, 46,000 pubs suddenly had a public advocate they didn’t have before.

For those building using these new tools, platform dependency hasn’t gone away. A creator on YouTube is beholden to changes to the algorithms and monetisation. The developer using ChatGPT to create an app faces Apple’s tax. Substack takes a slice from its writers’ subs.

Just because the playing field is being levelled doesn’t mean it’s now fair. But even here, alternatives are emerging. Nostr is proof of that: an online protocol that is manifesting as a type of decentralised social media with no owner or default algorithm.

Those on Nostr have the ability to send ‘zaps’ - the equivalent of micro-payments using Bitcoin.

This enables creator-to-audience and business-to-consumer payments that bypass platform middlemen. Learn something from a video? Zap them. Need help debugging a website? Zap them. Personal trainer? Zap them. You pay the person, not the platform hosting the exchange.

Nostr is far from mainstream. Most creators and businesses still rely on traditional platforms. Its emergence does show it’s possible and that the infrastructure for peer-to-peer, value-for-value exchange is being built. Whether it scales depends on whether people choose to use it.

Not everyone will take this path. And that’s fine. Some people prefer steady jobs and the structure and security that comes with it. I know, I’ve been there.

For people, however, that have that niggling feeling and an idea that they’ve been putting off, perhaps for fear of not knowing where to start, or the belief that they don’t have the financial means, or the technical skills and knowledge to build it, the conditions are changing.

The arrival and continued development of AI could remove some of what has been standing in their way, turning the question from ‘should I try?’ to ‘why not?’

AI won’t make failure any less painful. It may even make it more difficult to stand out by increasing competition. The disruptors will disrupt the disruptors. This dynamic has always existed though; those driven to try something will do so, regardless of the odds.

The old certainties - that a particular route would hold, that institutions would do what individuals couldn’t - no longer apply. The systems we are used to are being contested by the tools now available to anyone willing to use them. The result isn’t a world with fewer failures, but one with far more attempts.

For those paying attention to what’s now possible, the response is to try to create.